The Chaotic Origin Story of Visa That Nearly Collapsed the Banking System

The origin of Visa is rather dramatic. It started as a tangled experiment that many bankers wanted to shut down. The rules were unclear, and trust between banks barely existed. The system expanded faster than anyone had expected, and mistakes accumulated in public view. What survived that mess became one of the most unusual success stories in corporate history.

A Credit Card Program Nobody Knew How to Control

Credit: 89Stocker

By the late 1960s, Bank of America had a rapidly expanding credit card program, but it also faced problems. The company issued cards widely without vetting customers, resulting in massive unpaid balances and a rise in fraud. Worse, the bank couldn’t legally operate across state lines, so it began licensing the card to other banks.

Dee Hock Wasn’t Trained for This

Credit: flickr

That chaos eventually landed on the desk of Dee Hock, a manager at a small Seattle bank that was part of the BankAmericard network. He was not a traditional finance executive. His background was in history and philosophy, and he approached problems as systems rather than balance sheets. Tasked with dealing with a failing credit card operation, Hock did not focus on patching losses or tightening rules. Instead, he began to question whether the structure itself was fundamentally flawed.

Everyone Played by Their Own Rules

Credit: Reddit

At one point, more than 250 banks issued BankAmericards, but each one had different processes and legal interpretations. There was no shared fraud policy, no consistent way to settle disputes, and no enforcement mechanism when things went wrong. Banks blamed each other constantly, and customers got caught in the middle.

The Proposal That Sounded Like a Bad Idea

Credit: Facebook

Hock suggested that the credit card program be spun out as a separate entity, one not controlled by Bank of America but governed equally by all participating banks. For months, the idea sparked fierce resistance, but in the end, it was approved—mainly because no one had a better alternative.

A Business Structure That Flipped the Script

Credit: Getty Images

What emerged wasn’t a traditional corporation. In fact, it resembled a kind of organizational experiment. Instead of being owned by a parent company, the new network—eventually called Visa—was owned by its member banks. Decisions were made collectively. The center didn’t hold power over the parts; the parts made up the center.

The Technology Couldn’t Keep Up

Credit: Facebook

When Visa launched, its infrastructure still relied heavily on manual processes. As transaction volume exploded, the system came dangerously close to collapsing under its own weight. In response, Visa invested heavily in new technology platforms, Base I and Base II, which finally automated authorization and settlement.

Growth Wasn’t Always a Good Thing

Credit: Getty Images

As the network expanded, it became clear that scale was both an asset and a liability. More banks meant more volume, but also more potential for mistakes. A single misstep in one part of the system could affect thousands of transactions. Hock believed that this risk could be managed by letting innovations happen on the edges.

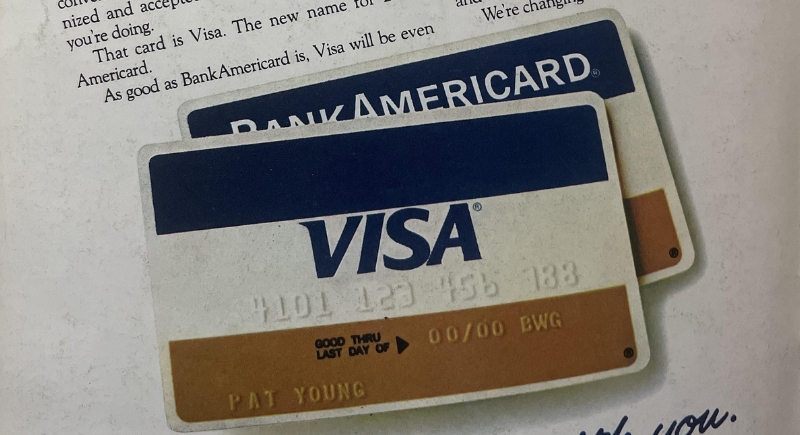

Visa Wasn’t Always Called Visa

Credit: Africa Images

Originally, the new organization went by the name National BankAmericard Inc., which did little to separate it from its troubled past. The name still implied ownership by Bank of America, which made other member banks uneasy. Rebranding to Visa in 1976 helped shift perception. The name suggested international access and neutrality.

Leadership Meant Knowing When to Let Go

Credit: Getty Images

Dee Hock believed the best thing leaders could do was define the purpose of an organization and then get out of the way. That approach baffled traditional managers who equated leadership with control, but it worked. People closest to the problems were trusted to make decisions, and that autonomy helped keep Visa adaptable.

The Near-Failure That Changed Everything

Credit: Getty Images

Visa’s survival wasn’t guaranteed. The early days involved real risk: technical failures, infighting, public skepticism, and regulatory heat. Yet instead of collapsing, the network adapted. It didn’t become a powerhouse by enforcing strict control; it grew stronger by letting its parts evolve.