If there’s one thing you can say about Kathryn Bigelow it’s that she doesn’t back down.

The enigmatic filmmaker is the first — and still only — woman to ever win the Academy Award for Best Director (2008’s “The Hurt Locker”). She makes brave choices in the scripts she brings to life (“Zero Dark Thirty,” “Detroit”), and possesses a keen eye for visual aesthetics and imagery (“Near Dark,” “Strange Days”).

But when people talk about Kathryn Bigelow, they tend to focus on the controversy surrounding some of her films or the movies that didn’t quite jolt the Tomatometer.

Fiercely independent in her life and her work, Bigelow is not your average wallflower, even if she claims to be seriously shy.

She was born and raised in Northern California. Her films bend toward macho genres and masculine themes, and she always elicits a lot of flack — some deserved, some misplaced — for her choices.

There seems to be little gray area with Bigelow. Maybe that’s because what we do know about her largely comes from her body of work. She is intensely private and somewhat confounding. She is also widely admired, deservedly so. And when it comes to art, no matter the medium, criticism is always following close behind.

Growing Up Fast

Bigelow accepts the John Schlesinger Britannia Award for Excellence in Directing during the 2013 BAFTA Los Angeles Britannia Awards in Beverly Hills, Calif. Matt Sayles / Invision/AP

Bigelow was born on Nov. 27, 1951 in San Carlos, Calif., and is the only child of Gertrude and Ronald Bigelow. She once told the Guardian that her folks took a rather progressive path to child rearing by letting Bigelow “make all my own decisions.”

“If a friend said, ‘Can you sleep over?’ I’d go to my parents and they’d say, ‘Well, it’s up to you,’” she said. “It was always up to me. It created a tremendous sense of independence.”

Bigelow’s parents were also creative. Her mother, a Stanford graduate, was an English teacher and librarian, while her father was a paint factory manager who also drew cartoons.

“His dream was being a cartoonist, but he never achieved it,” she said of her father. “I think part of my interest in art had to do with his yearning for something he could never have.”

That interest first led Bigelow to the San Francisco Art Institute in the late 1960s. She would then move to New York on a Whitney Museum fellowship, eventually ending up at Columbia University and finding her calling behind the camera.

Exposed to Brilliance

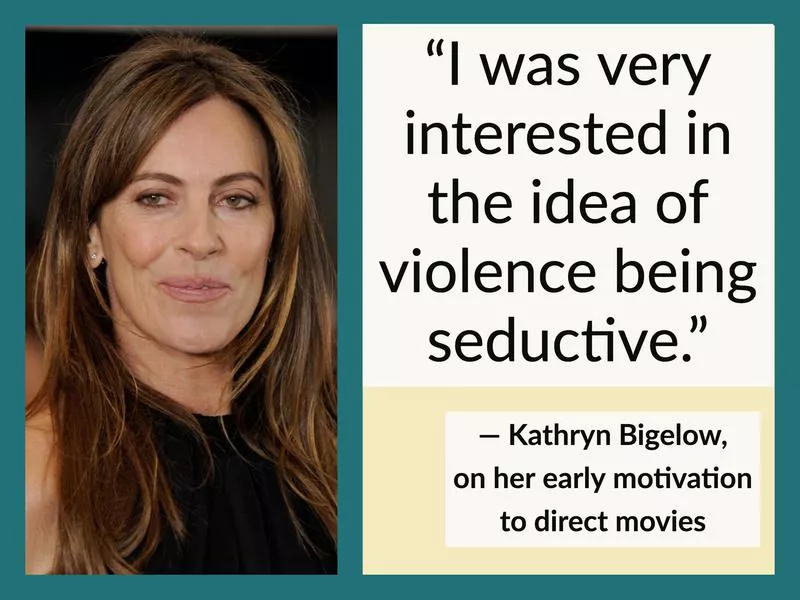

Under the Whitney fellowship in New York City, Bigelow would be exposed to some of the most dynamic minds in the art world. She counts Susan Sontag, Richard Serra, and Robert Rauschenberg among her professors. She struck up a friendship with composer Philip Glass, who was then a cabdriver, and the two began renovating and flipping lofts together. She worked for the legendary performance artist Vito Acconci, which is also when she discovered her taste for filmmaking.

“Somehow I commandeered a camera, got a crew of friends together, and shot something,” she told Interview magazine in 1989. “I was very interested in the idea of violence being seductive. Again, it was all from an analytical standpoint. I ran out of money and got a scholarship for graduate school at Columbia. Milos Forman was the co-chairman of the film division, and we had a lot of access. Peter Wollen was one of the teachers. He was great. He’s illuminating. Until I met him I was just looking at light reflected on a screen. After that it was more like a window.”

Bigelow made a short film called “Set-Up” in 1978 for her master’s thesis at Columbia (it’s now housed in the Museum of Modern Art’s cinema library). The 20-minute movie examines cinematic violence, with two actors actually beating up each other while Sylvere Lotringer and Marshall Blonsky, two prominent semioticians, discuss the images in voiceover.

Many have said the theme portends well to Bigelow’s later filmmaking choices.

This Is a Man’s World

Bigelow and Micheal Eric Dyson are interviewed on the red carpet before the premiere of “Detroit” at the Fox Theatre on July 25, 2017 in Detroit. Carlos Osorio / AP Photo

If 2017 taught us anything about Hollywood it’s that men dominate the landscape — and not in positive ways. Most high-profile Hollywood jobs go to men and he director’s chair is no exception.

When Bigelow first got behind the camera to make a feature film, she was entering largely uncharted territory for a woman (and it hasn’t changed much since). Her first movie was called “The Loveless” and it debuted in the U.S. in 1982, making her one of only a handful of women at the time to ever direct a Hollywood film.

That’s no exaggeration: There were 7,332 feature films made in Hollywood from 1939 to 1979, and of that total, according to the Directors Guild of America, only 14 were directed by women.

And it would be decades before Bigelow shattered the glass ceiling.

Un-Welcome to the Big Screen

Bigelow arrives at the premiere of the feature film “Zero Dark Thirty” at the Dolby Theatre in Los Angeles on Dec. 10, 2012. Dan Steinberg / Invision/AP)

Bigelow not only directed but also wrote “The Loveless.” It was also the debut of actor Willem Dafoe. Bigelow said inspiration for the movie came through her love of the Marlon Brando classic “The Wild Ones.” Both movies are about motorcycle gangs. In “The Loveless,” the bikers ruffle the feathers of a small Southern town while passing through en route to Florida.

The film received critical acclaim and soon Bigelow found herself in demand for more movies — although the offers were not necessarily what she expected. It seems Hollywood was all too aware of its history with male-dominated filmmaking and wanted to keep it that way.

In a 2009 article in the New York Times, Bigelow said that after “The Loveless” debuted and received positive reviews, she started getting scripts to consider. Only the scripts were nothing like the dark, postmodern, masculine script she’d written for “The Loveless.” Instead, she was sent teen comedies — a genre considered more apt for a female director.

“It was an intersection of absolutely inappropriate sensibilities,” she told the Times.

So instead of crawling into the pigeonhole, Bigelow left New York for a professorship at the California Institute of the Arts near Los Angeles.

Bigelow Is Born

Despite interest and offers from studios, Bigelow would not release another film for five years. However, it would be her career-defining work.

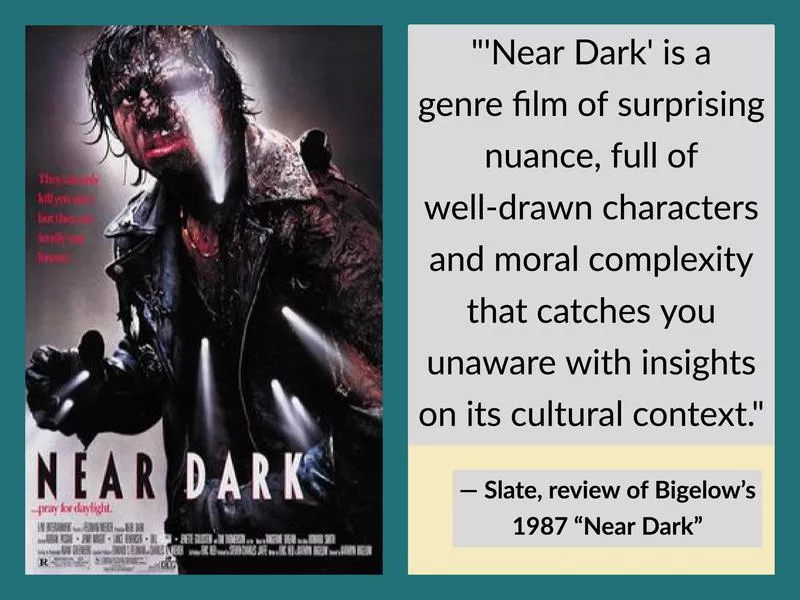

“Near Dark” came out in 1987 during a time when Hollywood was reviving the vampire genre, but doing so with campy hits like “The Lost Boys” and “Fright Night.” It never made much of a splash at the box office, but it’s widely considered one of the best vampire films ever made and a true cult classic.

The plot is simple enough: Set in Oklahoma, a young cowboy discovers the vampire underworld after meeting a mysterious woman who turns him into a vampire. He struggles to accept his new life as his father tries to find him.

As Slate put it, “Near Dark is a genre film of surprising nuance, full of well-drawn characters and moral complexity that catches you unaware with insights on its cultural context.”

For one thing, the word “vampire” is never said in the movie. In fact none of the usual tropes of blood-sucking beasts appear in “Near Dark.” What viewers do get is a blend of action, Western, and horror that looks beautiful and works seamlessly — an approach to filmmaking that would come to define Bigelow’s style.

It was also a particularly prolific time in Bigelow’s career, in which she would release three films in the span of four years.

More Movies and a Brief Marriage

The next two movies in Bigelow’s canon were “Blue Steel” in 1989 and “Point Break” in 1991. The two films could not be more different, except for the fact that they are both packed with action and suspense.

“Blue Steel” was also written by Bigelow and centers on a strong female lead. Jamie Lee Curtis stars as a rookie NYPD cop who fatally shoots a robbery suspect during her first week on the job, then becomes the object of affection for a murderous Wall Street broker. The film was notable for its climactic scene taking place in the middle of Wall Street itself.

“Point Break” is another of Bigelow’s cult classics, and it was mostly well-received upon release but did not do a ton of damage at the box office. It has become a cult classic in its own right thanks largely to its two stars. Keanu Reeves plays an undercover FBI agent who tries to infiltrate a Southern California surfer gang of prolific bank robbers, led by the late Patrick Swayze.

In the midst of both of these films, Bigelow would find time to marry her only husband.

Kathryn and James

Bigelow poses with her former husband James Cameron at the 15th Annual Critics Choice Movie Awards in 2010 in Los Angeles. Matt Sayles / AP Photo

In 1989, Bigelow married fellow director James Cameron. They had no children and would divorce a mere two years later. During the marriage, Cameron was working on the second “Terminator” film and apparently started an affair with that movie’s star, Linda Hamilton. They would later marry and also divorce after only two years.

Many cast Bigelow as a beneficiary of Cameron’s prowess — which sounds like yet another slight against a powerhouse female director that most likely came from a male perspective.

Nevertheless, for her part, Bigelow has never publicly berated Cameron for his actions. They are actually still friends. (Hamilton, on the other hand, is crystal clear about her feelings for the man they both divorced).

Part of slight against Bigelow when it came to Cameron was derived through the fact that he penned her next film, 1995’s “Strange Days.” It’s a bizarre sci-fi thriller noir that explores racism, voyeurism, abuse of power, and rape. Cameron actually wrote it in 1986 and did nothing with it, but Bigelow found new meaning in the story after the 1992 riots in Los Angeles and the Lorena Bobbitt trial.

But if revenge is a dish best served cold and nearly 20 years later on Hollywood’s biggest stage, Bigelow definitely got her just deserts (more on that later).

Breaking Through

Actor Jeremy Renner and Bigelow arrive for the screening of “The Hurt Locker” at the 65th Venice Film Festival in Venice, Italy in 2008. Joel Ryan / AP Photo

Bigelow would enter the new millennium with two lackluster films, “The Weight of Water” (2000) and “K-19: The Widowmaker” (2002), before her historic turn with the Iraq war drama “The Hurt Locker” in 2009.

It also marked the first of her three collaborations with screenwriter Mark Boal, and it took several years for everything to come together.

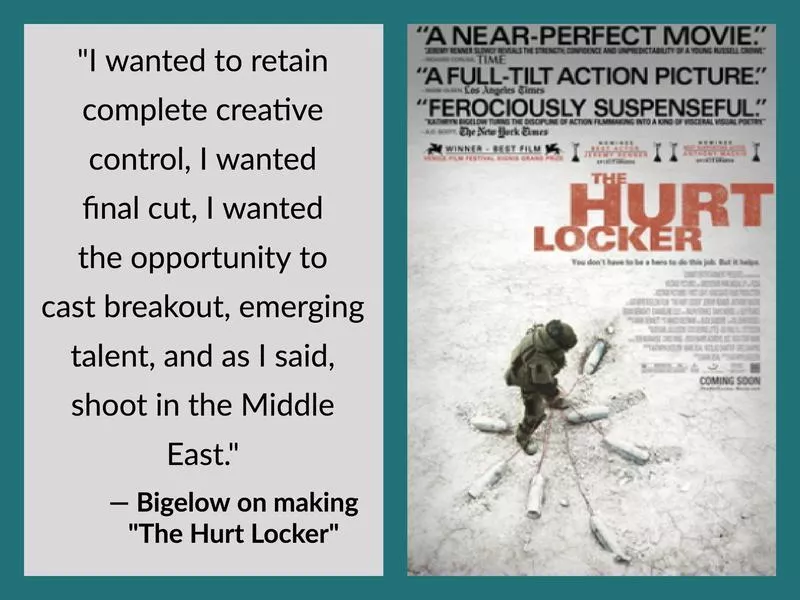

“The Hurt Locker” follows three U.S. military bomb technicians during several missions around Baghdad. Some people argue it’s the greatest war movie of all time. Others say it’s visually stunning and a highly accurate portrayal of life in a battle zone. Everyone agrees it’s a damn good movie.

As with her other films, the little things ended up having big impacts in “The Hurt Locker.” For instance, Bigelow opted against using well-known actors, saying the choice buoyed “the suspense of not knowing who’s going to live. There’s a conventional reaction when you see a star: You anticipate he’ll be a part of a particular denouement down the road, so you don’t worry for that character. In ‘The Hurt Locker,’ after the first sequence, you realize all bets are off.”

Bigelow also said she was attracted to “the way the script portrayed heroism and courage — not as a cartoonish quality, or an absence of fear, but as a certain kind of resilience in the face of fear.”

Her Greatest Success To Date

Filmed in Jordan, Bigelow had a few heavy doses of reality during production. Near the filming location in Amman was an Iraqi refugee camp with people who had been prisoners of American forces. Among them were many actors, so Bigelow cast them as extras for the film playing war prisoners — an irony not lost on Bigelow.

And like all her films, “The Hurt Locker” is independent in the true sense of the word. Her movies might be released by big studios, but the actual production is never within those confines.

“We never approached any other financing avenue,” she told The AV Club. “I wanted to keep it as independent as humanly possible, and I wanted to shoot in the Middle East. That alone probably would have been a non-starter. And then I anticipated that and didn’t pursue. And also, to be honest, I’ve never made a non-independent movie. No matter what scale it’s been, it’s always been independent. So I wanted to retain complete creative control, I wanted final cut, I wanted the opportunity to cast breakout, emerging talent, and as I said, shoot in the Middle East.”

Shattering the Glass

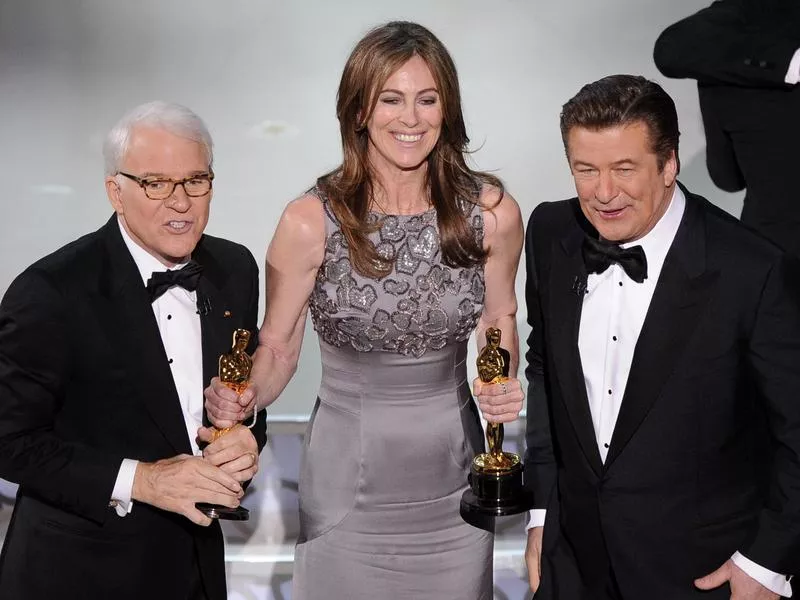

Bigelow holds her Oscars for best motion picture of the year and best achievement in directing for “The Hurt Locker” with hosts Alec Baldwin, right, and Steve Martin at the 82nd Academy Awards in 2010. Mark J. Terrill / AP Photo

Not only was “The Hurt Locker” a cinematic and box office triumph, it also won oodles of big-time awards — including several firsts for a woman director.

After garnering nine Oscar nominations in 2010, it won six: Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay, Best Sound Editing, Best Sound Mixing, Best Film Editing, and Best Director. It also won six BAFTA awards, and Bigelow was the first woman to win the Directors Guild of America’s top honor for directors.

Most noteworthy in the awards haul was the Academy Award for Best Director. Bigelow remains the only woman who has ever won it. In fact, only three other women have ever been nominated: Lina Wertmuller (“Seven Beauties,” 1975), Jane Campion (“The Piano,” 1993), and Sofia Coppola (“Lost in Translation,” 2003).

And as if the honor itself weren’t enough, Bigelow beat out her ex-husband, James Cameron, who was nominated for “Avatar.”

“There is no other way to describe it — this is the moment of a lifetime,” she said after accepting the Oscar.

Living Legend

“The Hurt Locker” was a turning point. Even though she’d been making movies for decades, it was as if the world had just discovered Kathryn Bigelow. Or, perhaps, she had given American audiences something they weren’t ready for, even if she also received the industry’s top prizes.

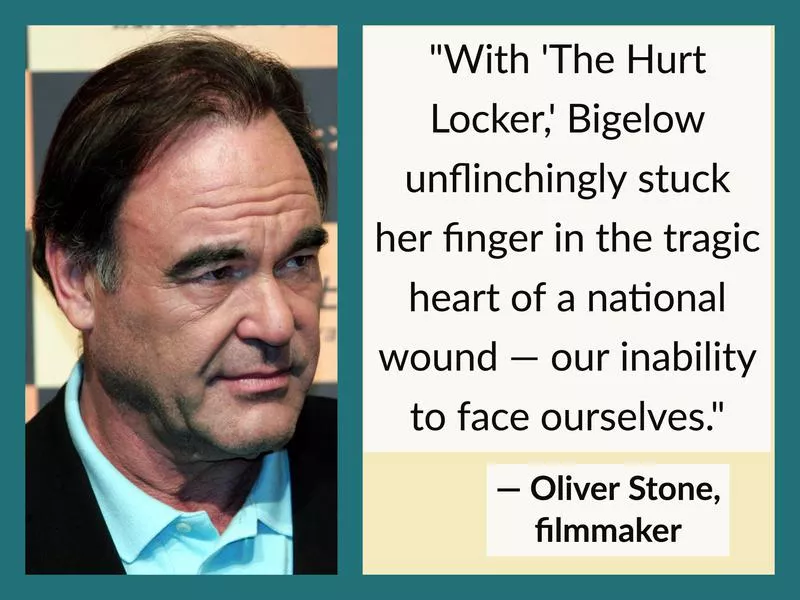

The same year Bigelow won the Best Director Oscar, Time magazine named her one of the 100 most influential people in the world.

Filmmaker Oliver Stone, writing for the magazine, said of Bigelow that “[d]espite enormous accolades, [“The Hurt Locker”] is considered a financial failure — like all films about the Iraq war. The question lingers: Why, despite our country’s love affair with violence, do Americans refuse to see these realistic films? With The Hurt Locker, Bigelow unflinchingly stuck her finger in the tragic heart of a national wound — our inability to face ourselves.”

Bigelow became the director to watch — and that meant the scrutiny would only get worse.

Under a Microscope

Bigelow stands on the set during shooting for “Zero Dark Thirty” about Osama bin Laden in Chandigarh, India, in March 2012. Anil Dayal / AP Photo

Bigelow again teamed up with screenwriter Mark Boal for her next project, 2012’s “Zero Dark Thirty.” The film is a political thriller about the 10-year quest to capture Osama bin Laden following 9/11.

Almost universally lauded by critics and a huge box office success — it was No. 1 during its first weekend of wide release and also grossed more than $132 million worldwide during its entire run — “Zero Dark Thirty” nonetheless generated a massive amount of controversy.

Most of the criticism centered on Bigelow’s directorial choices concerning CIA interrogation techniques and the killing of bin Laden, which actually happened while the film was being shot. Were they interrogation techniques or torture, and is this movie playing them down so much that it’s actually endorsing torture?

Some felt the film glossed over waterboarding and other forms of interrogation the CIA claimed were integral in finding bin Laden and made it seem like those forms of interrogation were far more important than they actually were.

Bigelow was also criticized for not condemning the controversial interrogation techniques, particularly by The New Yorker. Longtime staff writer Jane Mayer wrote that if Bigelow “were making a film about slavery in antebellum America … the story would focus on whether the cotton crops were successful.”

To her credit, Bigelow took the criticism in stride.

“Where there’s clarity in the world, there’s clarity in the film. Osama bin Laden was killed in Abbottabad, Pakistan — that’s clarity. And where there’s ambiguity in the world, there’s ambiguity in the film,” she told Time magazine in 2013. “If you look at the experts on the subject matter, whether it’s Mark Bowden [author of The Finish: The Killing of Osama bin Laden] or David Ignatius [of the Washington Post], they all say that some information came out of the detainee program. Maybe once the Senate report is declassified, we’ll have more information. Maybe advocating a little more transparency in government would be a healthy step.”

Keeping Her Private Life Private

Bigelow and Mark Boal arrive at the 70th Annual Golden Globe Awards in 2013 in Beverly Hills, Calif. Jordan Strauss / Invision/AP

No Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram. No formal website even. Kathryn Bigelow is something of an enigma when it comes to modern ways of communicating, at least online.

We do know the nearly 6-foot tall filmmaker was married to James Cameron, briefly and a long time ago. We know she has no children. We know she is a painter and art lover. We know she carefully chooses her film projects, sometimes going years and years between productions.

But other than that, who is Kathryn Bigelow?

After “Zero Dark Thirty” was released, Bigelow and screenwriter Boal started heavily promoting the film for awards season. If it’s celebrity gossip you seek, this Hollywood Reporter story about Bigelow and Boal should provide some relief. It doesn’t explicitly say the pair dated, but it more than implies such.

Another Bold Choice

Moviegoers arrive at the Fox Theatre in Detroit for the premiere of 2017 film “Detroit,” about the rioting and civil unrest that tore apart Detroit during the summer of 1967. (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio) / (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio)

And another bad reaction.

Bigelow’s latest film is “Detroit,” released in 2017. It revisits a particularly disturbing incident at the Algiers Motel during widespread rioting and civil unrest in the summer of 1967.

Again the film received widespread acclaim. And again it also generated a lot of controversy.

Fighting Back

Bigelow on the red carpet before the premiere of “Detroit” at the Fox Theatre. Carlos Osorio / AP Photo

Due to the racially charged subject matter, some have said a white woman should not have made the movie. Angelica Jade Bastien wrote that she’s “not interested in white perceptions of black pain,” and the movie was “directed, written, produced, shot, and edited by white creatives who do not understand the weight of the images they hone in on with an unflinching gaze.”

Others pointed out that the film is so important today because “[n]ot many stories set 50 years in the past speak so clearly to the right now.”

Bigelow acknowledged the criticism, but didn’t dwell on it. She told the Guardian “that the most important thing is to tell this story and get it out there.”