To this day, the Great Depression is the worst economic downturn the world has ever seen. Almost overnight, millions of Americans went from raucous Roaring ’20s parties in speakeasies to cobbling together cardboard houses on the street.

These photos from the Great Depression offer a look into the people who lived during these times and what they had to do to survive. The historic photos are not just of breadlines and Hoovervilles, but also of veterans clashing with police, great dust storms, striking farmers and migrant workers struggling to make ends meet. Through these snapshots, we can glean a history of America’s bleakest era.

The Great Depression lasted 10 years. This is what it looked like and what we can learn from that tumultuous time.

What Was the Great Depression?

AP Photo

Reasons for the Great Depression can vary among economists, but several factors aren’t argued. Perhaps most importantly, wild speculation and consumer overconfidence bolstered by the Roaring ’20s inflated stock prices beyond reason. The average worker borrowed on margin, letting just about anyone — including those with not enough money — to borrow and buy stocks. Some people were only putting down 10 percent of the share value.

At the same time, an agricultural recession went ignored and the Fed hiked interest rates by 1 percent a few weeks before the stock market crash, which caused further instability in the market. Then, when the market finally crashed, there was a mad rush to withdraw money from the banks. But those banks didn’t have the cash to give back, because they too had invested in the market. By 1933, roughly half of America’s banks were dead.

Above: Around 5,000 people lined up for employment relief in New York City on Nov. 24, 1933.

October 24, 1929 — Black Tuesday

AP Photo

People gather on the sub-treasury building steps across from the New York Stock Exchange in New York on Black Thursday, Oct. 24, 1929.

Black Thursday is the day that kicked off the Great Recession, but stock market troubles had been brewing six weeks before then. The market closed at its record height at 381.2 on Sept. 3, 1929, but trended downward, and as it did, more and more people sold their stocks, causing the market to fall more and more. By Black Tuesday, the Dow hit 230.07, down 12 percent the day before.

It kept falling, too. The market fell to its lowest point on July 8, 1932, closing at 41.22. It had lost 90 percent of its value since its height.

Breadlines Began Fast

AP Photo

For some, the Great Depression started immediately. Within a few months or less, bread lines had to be opened. Above, early victims of the Great Depression wait for food in New York City’s Lower East Side on Jan. 1, 1930. It was just a hint of things to come.

Food lines during the Great Depression are interchangeably called breadlines, although bread usually wasn’t what they gave out. “Breadline” may have been coined by the Vienna Bakery in New York City in 1876. Instead of throwing out old bread, the bakery owner would hand it out to the homeless who lined up outside.

Millionaires Went Bankrupt Overnight

AP Photo

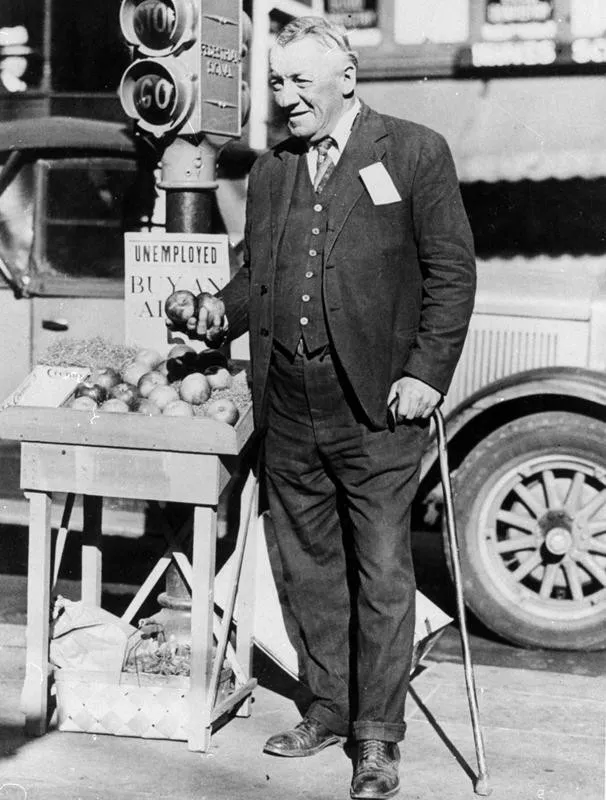

The Great Depression brought the wealthy to shacks and newspaper blanket nights just like everyone else.

Pictured here is Fred Bell, a man who invested enough of his $75,000 inheritance into the stock market to become a multimillionaire in the 1920s. Known as “Champagne Fred” during better times, he was reduced to selling apples on a street corner in San Francisco, California.

“Now I have nothing except these,” Bell told the Healdsburg Tribune in 1931, pointing to a box of apples at his feet. “But do you know I really think I have something: I never had before, a kind of happiness, if you know what I mean.”

This photograph was taken on March 7, 1931. Bell was 57 years old. He died in a poor house in 1934.

‘I Am for Sale’

AP Photo

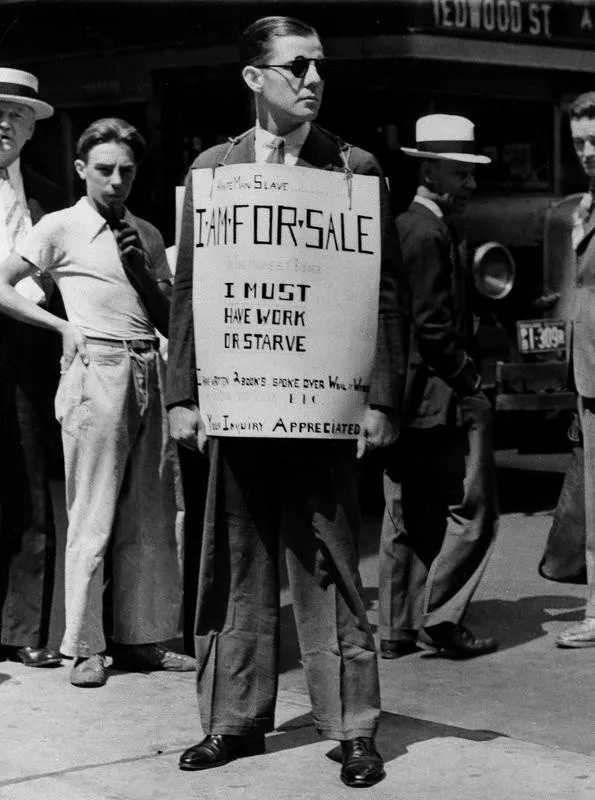

As the Great Depression continued, more and more Americans were out of work. By 1931, the unemployment rate was at 15.9 percent.

In this photo, 30-year-old Robley D. Stevens wears a sign that reads: “I am for sale. I must have work or starve,” while standing on a sidewalk in Baltimore, Maryland in August 1931.

Looking for Any Opportunity

AP Photo

Any mention of jobs would summon thousands of men willing to work. This photo was taken on Oct. 9, 1930, outside Cleveland’s City Hall.

About 2,000 jobs were made available for city park improvements, a rare opportunity in such dark times.

Protests Erupted Around the Country

AP Photo

Across the country, protests and small riots broke out. In this photo, some 1,000 out-of-work people march on San Francisco City Hall on Jan. 19, 1931, to protest wage cuts. On the podium is San Francisco Mayor Angelo Joseph Rossi, who said he would answer their demands publicly but not at all. The crowd, wanting a delegation to be heard, were denied one. They also didn’t let him speak.

Rossi was an ardent anti-Communist who called on the California governor to send in the National Guard during the 1934 West Coast Waterfront Strike, which led to the death of two workers. In 1942, he was accused of being a fascist and was defeated for reelection in 1943.

Hunger Marches

AP Photo

Many of the protests during the Great Depression era came in the form of hunger marches, a form of protest where people march in solidarity from one place of high unemployment to a place of governance. Sometimes people walked for days. One group walked from New Jersey to Washington, D.C.

In the United States, these protests were composed of people who demanded things like unemployment insurance, cash payments, free utilities and free lunch for children.

This photo was taken on Nov. 22, 1932, in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Hunger marchers swarmed the Minneapolis City Hall but were met by police guarding the doors. Fighting ensued, and 18 people were arrested.

Women’s Emergency Brigade

AP Photo

The Women’s Emergency Brigade was established in Flint, Michigan in January 1937.

The Brigade was formed by wives and relatives of General Motors auto workers who were on strike because of horrible working conditions and low wages. Workers sat down and occupied the GM plant.

The Brigade was there to protect the strikers, and they meant business. The women carried clubs and wore berets and armbands with EB on them to signify they were ready to fight. One of the Brigade’s founders was quoted in The New York Times saying, “We will form a line around the men, and if the police want to fire then, they’ll just have to fire into us.”

There were two other chapters in Lansing and Detroit. The Brigades were temporary but was a sign of a new wave of feminism.

This picture was taken outside of a Chevrolet plant in Flint, Michigan on Feb. 2, 1937.

Dairy Farmer Strikes

AP Photo

Beginning in 1933, dairy farmers demanded higher prices for milk and staged aggressive and sometimes violent strikes.

In Wisconsin and other states, pickets stopped milk trucks and put down tire breakers to prevent dairy deliveries. They vandalized cheese factories, threw rocks through grocery store windows and sometimes overturned delivery cars carrying milk. The worst strikes happened in Wisconsin, where several people died, and cheese and dairy factories were bombed.

In this photo, striking dairy farmers dump milk from a truck on its way to a plant in Boonville, New York, on Aug. 19, 1939.

The Dust Bowl

AP Photo

Further exacerbating the Great Depression was the Dust Bowl, which began in 1930 with severe droughts across the Great Plains. By 1931, miles and miles of parched fields sowed and an again by untrained farmers had turned to dust.

Dust clouds that stretched to the heavens propelled by strong winds ripped across the Midwest, engulfing entire towns. Living with the dust became part of daily life.

In this photo, a farmer in Garden City, Kansas, is photographed on March 30, 1935. He is standing near livestock that were unable to graze and starved to death. He was unable to afford animal feed to make up for the barren landscape.

‘The Nightmare Is Becoming Life’

AP Photo

The worst of the storms in the Dust Bowl was known as Black Sunday, an immense dust storm on April 14, 1935, that is estimated to have blown some 300 million tons of topsoil from the Oklahoma panhandle to Amarillo, Texas, and beyond.

“The impact is like a shovelful of fine sand flung against the face,” Avis D. Carlson wrote in a New Republic article. “People caught in their own yards grope for the doorstep. Cars come to a standstill, for no light in the world can penetrate that swirling murk. … We live with the dust, eat it, sleep with it, watch it strip us of possessions and the hope of possessions. It is becoming Real. The poetic uplift of spring fades into a phantom of the storied past. The nightmare is becoming life.”

This photo was taken a day after Black Sunday, on April 15. It shows a ranch in Boise City, Oklahoma, about to be engulfed in a black cloud of dust.

Migrating to California

AP Photo

Many people left dust-buried prairies and migrated to California, looking for work.

This is a photo of a makeshift house built on wooden platforms in a camp for Dust Bowl migrants near Marysville, California, taken on May 18, 1937.

Children During the Great Depression

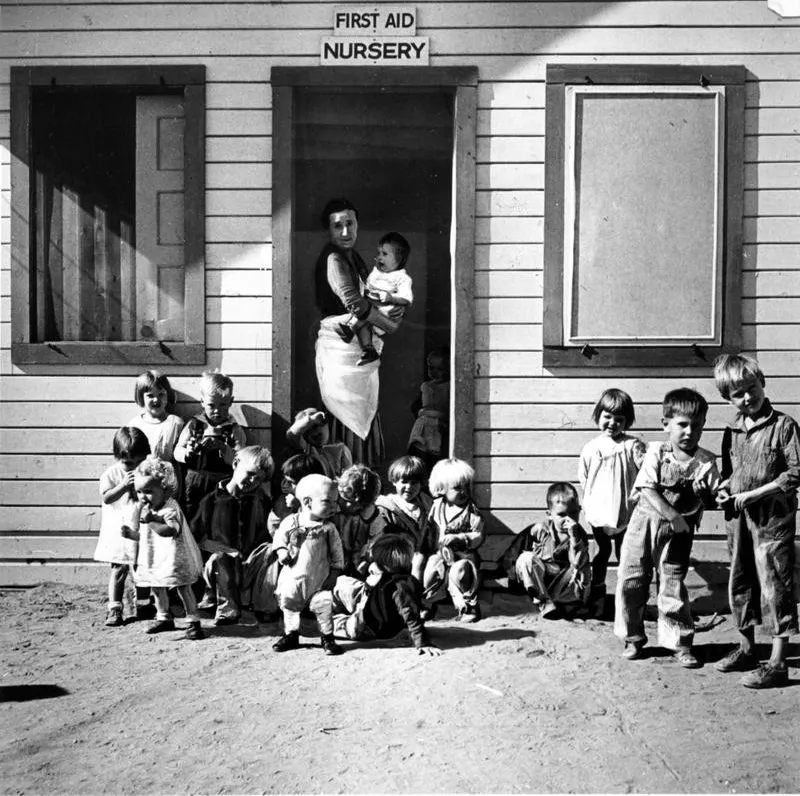

AP Photo

In 1933, the average family income was $1,500, down from $2,300 in 1929. Children suffered greatly under such duress. Families lived not only in the shacks of Hoovervilles, but wherever they could find shelter.

In Oakland, California, families lived in a network of unused, above-ground sewer pipes. Many families crammed into one-room ramshackle houses in squalid conditions. Families were abandoned by fathers and mothers. Sometimes children left home.

By 1940, more than 200,000 homeless children wandered the country.

In this photo, a nurse cares for the children of migratory farmworkers in Arvin, California, on Jan. 18, 1937.

A Christmas Meal

AP Photo

At the beginning of the Great Depression, there was no real federal aid for the unemployed and hungry. Food stamps would not be a thing until 1939. People had to depend on state and local governments for assistance, and, since that would never be enough, people depended on one another.

This is a photo of homeless and out-of-work men at a place called the Tub in New York City. The Tub was a soup kitchen run by a philanthropist named Urbain Ledoux, a humanitarian Baháí who fed unemployed workers and veterans after World War I.

This picture was taken on Dec. 25, 1931. The Christmas meal served was a stew made of turkey, chicken, goose, and squab. According to AP at the time, almost 5,000 people partook and had some of the food.

The Mexican Repatriation

President Hoover deported about 1.8 million Mexican-Americans for supposedly stealing American jobs. Under the dog-whistle slogan of “American jobs for real Americans,” the Hoover administration passed laws to prevent Mexican-Americans from holding jobs at both federal and local levels regardless of their citizenship.

Law enforcement raided Mexican communities and rounded up people wherever they gathered, demanded proof of citizenship and legal entry. Those who couldn’t were crammed into a van and sent to the border for processing and deportation. One researcher found that 60 percent of the 1.8 million Mexicans deported during the 1930s were U.S. citizens.

FDR didn’t ban the repatriation programs, and they did not die out until World War II. Then the government decided that Mexicans were good for America, because the country needed them for war.

The above photo was taken by Dorothea Lange in 1936. It shows a family of Mexicans with car trouble on the side of a road.

Mile-Long Food Lines

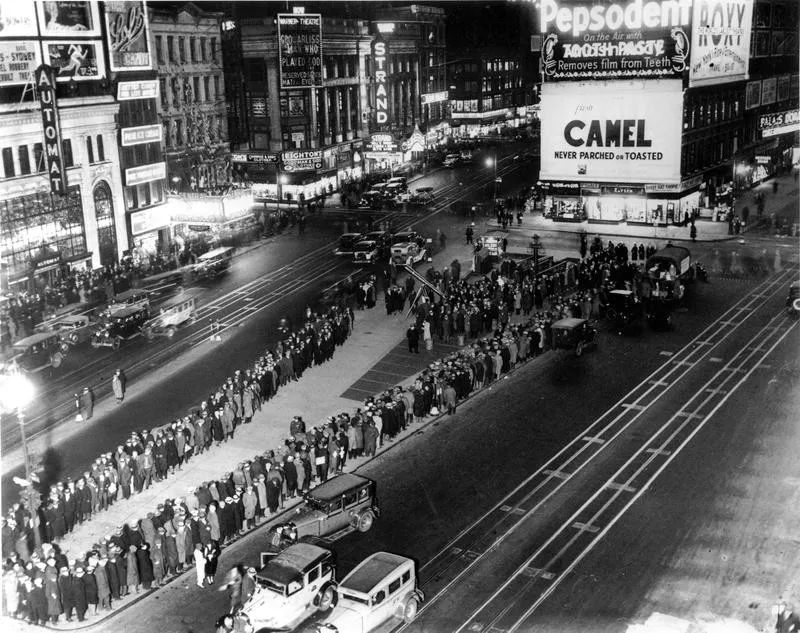

AP Photo

A mile-long line of men wait along Broadway in New York City for their ration of a sandwich and a cup of coffee in Times Square on Feb. 13, 1932.

In order to try and reduce the federal deficit, Hoover signed the Revenue Act of 1932 which increased the top income tax rate to 63 percent. It made the economy even worse. A month after signing the bill, the Dow bottomed out.

Two years prior in 1930, Hoover had signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which raised tariff rates and helped usher in the Depression.

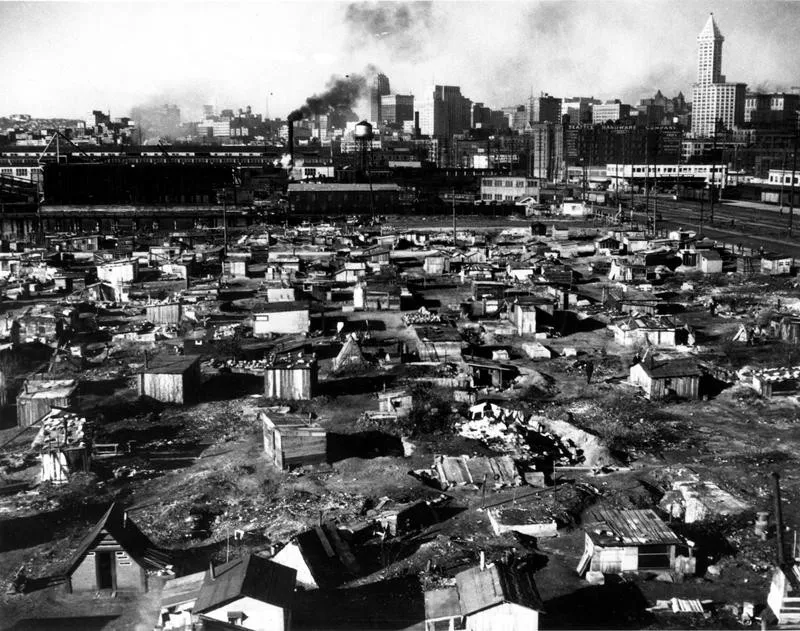

Hoovervilles

AP Photo

Hoover was so detested that the ramshackle tents and shacks which popped up along rivers throughout the nation were nicknamed Hoovervilles, a phrase coined by a newspaper reporter in 1930.

These homes were made with discarded materials, cardboard, tar, sheet metal, packing boxes, straw or whatever other scrap was available. Life in a Hooverville was grim.

This photo was taken on March 20, 1933, in Seattle, Washington. 1933 was the worst year of the recession with more than 15 million people — 25 percent of the workforce — unemployed.

Hoovervilles Were Tolerated … Usually

AP Photo

Hoovervilles were often tolerated and its residents sympathized with, although not always.

Some city officials ordered the burning of these tent cities, which is what happened in this photo. This picture was taken on Oct. 27, 1932, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Men were given a notice to vacate order from the city but did not, so their places were burned. They were redirected to a homeless shelter to spend the winter.

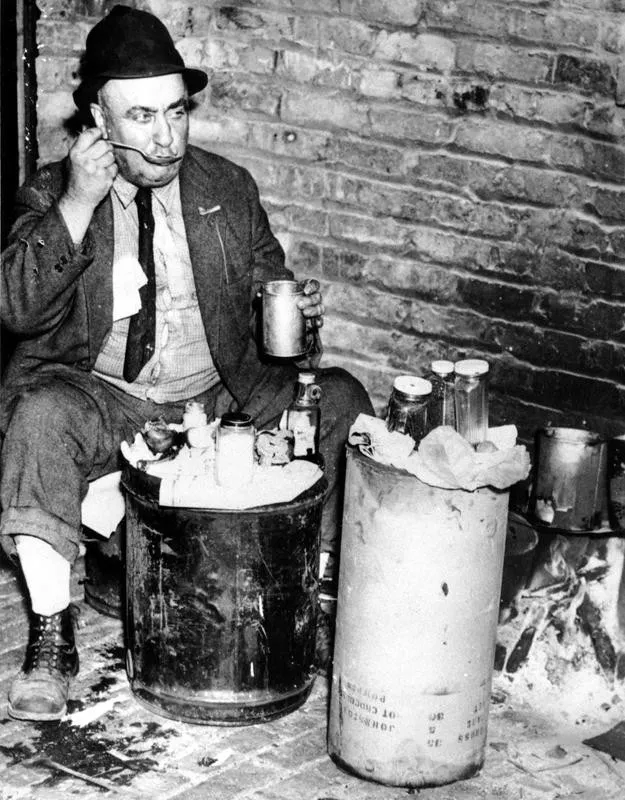

‘Nobody is Actually Starving’

AP Photo

“Nobody is actually starving,” Hoover told reporters in 1932, when the country was deep into the Great Depression and millions depended on soup kitchens to survive. “The hobos, for example, are better fed than they ever have been. One hobo in New York got 10 meals in one day.”

Along with tent cities being called Hoovervilles, empty upturned pockets were called Hoover flags. Hoover leather was cardboard used to line a shoe. A Hoover wagon was a car with its engine removed and horses hitched to it.

In the photo above, a former cigar maker named Albert Wendt cooks food on the streets of Chicago on June 22, 1938.

Communism Gains Popularity

AP Photo

Given the absence of any federal support and the inability of local governments to help its people, it’s not surprising that the Communist Party found new support. It also gave a convenient reason for the government to enact harsh and brutal responses of rebellion in the name of democracy.

The AP photo is captioned thusly: This aerial view shows Communist protesters and radical sympathizers gathered in Union Square in New York City, Aug. 1, 1932. The estimated crowd of 10,000 men, women and children are demonstrating against war.

Rise of the Bonus Army

AP Photo

A war veteran sleeps on the sidewalk by his wife on the streets of Washington, D.C., on July 29, 1932. They both had been evicted.

War veterans had a unique role in the Great Depression. The Bonus Act of 1924 granted World War I veterans a bonus of up to $500 for those who served stateside and up to $625 for those who served overseas. However, many of these bonuses could not be collected until 1945.

Thousands of war veterans united to form the Bonus Army, a group protest group that demanded early payout of the bonus they desperately needed now.

The Bonus Army Clashes With Police

Some 17,000 war veterans descended on Washington, D.C., in mid-1932 to demand early payouts of the bonuses owed to them.

The Bonus Army, along with their families and other protest groups, set up a Hooverville near the Anacostia River. The makeshift community numbered around 10,000.

On June 17, protesters waited anxiously on a bill approving early bonus payments. It had easily passed the House. But it died in the Senate, where it was overwhelmingly voted down. Hoover himself directed Congress to vote out the bill, believing that its $2.4 billion cost was too expensive.

On July 1932, Hoover ordered the removal of the Bonus Army and their Hooverville. The Bonus Army fought hard with police, and two veterans were shot and killed.

Federal Troops Burn the Bonus Army’s Tents

AP Photo

After the shooting — and unfounded fears that the Bonus Army would turn into a Communist uprising — Hoover sent in the Army.

Maj. George Patton led the cavalry and Gen. Douglas McArthur commanded 1,000 infantry and six tanks. The troops shot teargas into the protesters and drove them back into their pathetic huts. When a spectator shouted “The American flag means nothing to me after this,” Gen. MacArthur reportedly instructed his troops to arrest the man if he spoke again.

This photo shows a federal troop walking among the burning Hooverville along the Anacostia River on July 29, 1932.

Hoover Seals His Fate

AP Photo

The protesters were given an hour to evacuate their homes before the tents were methodically gassed and set ablaze. In the morning, nothing was left.

Hoover’s decision to act in such a brutal and inhumane way was deeply unpopular and a contributing factor to the landslide victory of his opponent, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The general election was held just five months later. The incident was fresh in the public’s memory.

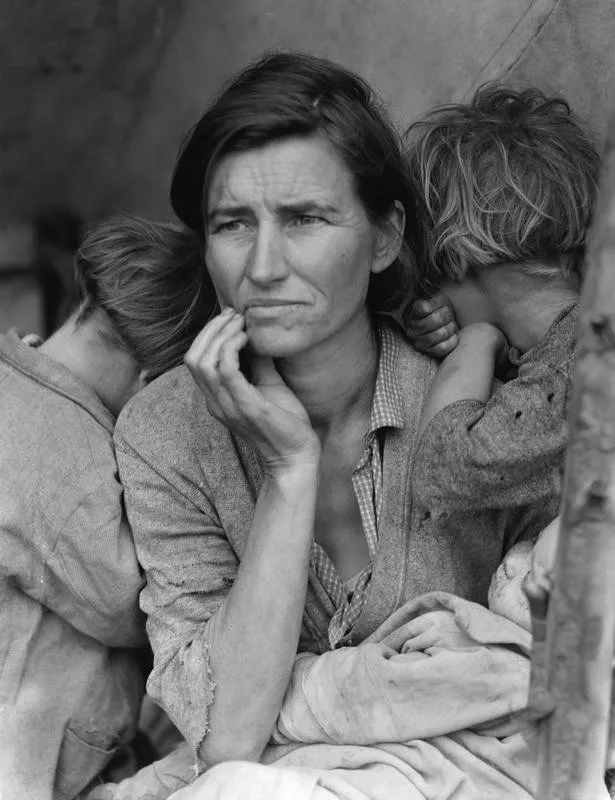

Migrant Mother

Dorthea Lange/Library of Congress / Wikipedia

“Migrant Mother” by Dorothea Lange is one of the most famous photos in American history. It was taken in March of 1936 in Nipomo, California. Twenty-four years after snapping this iconic photograph, Lange said this of her experience:

“I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions.

I made five exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction. I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food.

There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.”

Migrant Workers Slept in Fields

Dorthea Lange / AP Photo

A photograph by Lange shows migrant workers inside a pickup truck in central California on April 5, 1939.

Farmers who lost everything and were forced to move were called “Okies” because roughly 20 percent of them were from Oklahoma. But California was also suffering from the Great Depression and the influx of workers oversaturated the labor pool, creating poverty wages.

Migrant workers — who often brought their entire family — would move from one place of harvest to the next, having to constantly move around. They often set up camp in farmer’s fields near irrigation ditches.

Breadlines Continued into the Late 1930s

AP Photo

While the Great Depression is considered to have ended by the late 1930s, the unemployment rate was 15 percent in 1940. In November 2020, the unemployment rate in the U.S. was 6.7 percent.

In this photo, which was taken in Cleveland in May 1938, parents and children stand in line waiting for potatoes and cabbages sent in by the federal government. Local funds supplying 78,000 with direct relief had been exhausted.

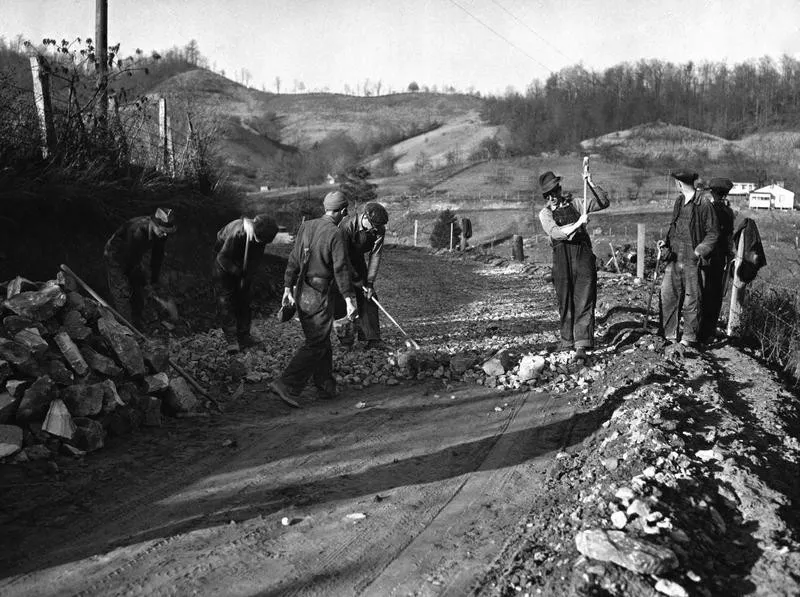

Revitalizing the Economy

AP Photo

The New Deal established the Public Works Administration, which the government poured billions of dollars in to build new roads, dams, bridges, schools, hospitals and other public infrastructure. At least three million people received jobs because of the PWA.

This photo of PWA workers building a road was taken in Dickenson County, Virginia, in July 1939.

FDR Signs the Emergency Banking Relief Act

AP Photo

On March 9, 1933, FDR signed the Emergency Banking Relief Act.

The bill was designed to restore consumer confidence and enough trust in the banks that people would take their cash from underneath their mattresses to the teller window. The bill strengthened federal regulations on banks and created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

This was an emergency bill that would be succeeded by the 1933 Banking Act, often referred to as the Glass-Steagall Act. The Glass-Steagall stopped commercial banks from investment banking so banks would not be able to use their credits to speculate on the market.

That bill was repealed in 1999 by the Gramm-Leach-Biley Act. Some believe its repeal contributed to the Great Recession.

FDR’s New Deal certainly helped, but it wouldn’t be until the 1940s and the post-war boom that America would return to and then surpass its GDP from its height in 1929.