For decades, the mantra of retirement advisers has been that people need to start saving early and often for a happy retirement.

But it’s only been in recent decades that they have turned their attention to how to best manage those savings once you’re no longer accumulating wealth and living off the proceeds of a life’s work.

The focus on making sure you don’t run out of money before you run out of years started in 1994 when William Bengen developed the “safe withdrawal rule,” more commonly known as the “4 percent rule.”

The 4 Percent Rule

Bengen looked at investment returns dating back to 1926 and concluded that if retirees had a portfolio made up of 50 percent stocks and 50 percent bonds, they could withdraw 4 percent of the balance annually and not worry about running out of money.

Bengen’s 4 percent rule was successful because it was simple. The problem is the investment landscape has changed dramatically since 1994, but people still quote Bengen’s rule as the only strategy you need to know to successfully plan for retirement.

Work + Money spoke with financial advisers who said that while the 4 percent rule is still a good way to conceptualize how to set retirement savings goals, it will require more nuance than just etching a percentage in stone to make it work for you.

How Much Money Do You Need?

As David Chwalek of Senes & Chwalek Financial Advisors in Concord, Mass., sees it, there’s only one right answer when people ask how much money they need to save before they can retire:

It depends.

“Everyone’s vision of retirement is different,” Chwalek said. “Some of our clients retire in the same home they’ve lived in for 40 years and spend their retirement years seeing their grandchildren, gardening and occasionally going out to eat. Others spend their money on a second home in Florida or expensive vacations.”

That means being realistic about retirement plans and figuring out how much you need for the retirement you envision. Chwalek says the 4 percent rule is still a good starting point on how to manage spending. But there are many caveats.

Market Fluctuations Matter

“If a retiree begins 4 percent retirement withdrawals from accounts that are invested aggressively and the stock market drops sharply for a year or two, their retirement income could be in jeopardy,” he said. “If, on the other hand, they have a few years of income set aside in cash or conservative investments, then they will be better positioned to withstand the short-term market declines.”

Planning Your Retirement Budget

Predicting the future is tricky, according to Chris White, author of “Working with the Emotional Investor: Financial Psychology for Wealth Managers.” Unlike your monthly household budget, which has fairly predictable costs, it’s hard to know how much healthcare will cost next year, much less a decade or more in the future.

It’s also hard to know how much you will be able to rely on Social Security, pensions and other non-investment income streams that retirees use when considering the 4 percent rule.

Concerning Social Security

“Social security income may or may not be a significant source of income due to its increasingly being taxed away,” White said. “Pensions are invaluable. But if they are not inflation-adjusted, then today’s pension payment won’t be worth as much ten years from now.”

Concerning Healthcare Costs

The only assumption retirees can make about healthcare inflation, White said, is it will outpace overall inflation. He recommends researching healthcare costs over time in the area of the country you plan to retire to.

“Lay out a projection of major expenses going forward over your retirement years.” White said. “Plug those into what you can expect from your portfolio and see how you do year by year.”

Why the 4 Percent Rule May No Longer Work

All of the advisors we spoke to noted that the 4 percent rule is based on a time when bond yields were higher and more predictable. Brian Saranovitz, co-founder of Your Retirement Advisor, said the 4 percent rule may not work in today’s markets if people follow the traditional recommendation of a portfolio made up of 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds.

The reason, he said, is that bond yields are at a historic low, and 4 percent will end up burning through the portfolio too quickly. For safety, he recommends an annual draw of 2-3 percent.

Saranowitz said retirees looking to still withdraw 4 percent each year may want to consider a combination of stocks and fixed indexed annuities. Sarnowitz developed such a plan, which he calls a Multi-Discipline Retirement Strategy, which includes a portfolio of globally-diversified stocks and annuities.

It’s “a combination critical as one approaches retirement,” Sarnowitz said. “It should also be coupled with a [systematic withdrawal income plan] and a buffer strategy in times of severe stock market losses.”

Retirement Risk Factors

Retirement Risk Factor #1: Living Too Long

Sarnowitz outlines several risk factors that impact portfolios and make the 4 percent rule unfeasible. Longer-than-expected retirements are becoming the norm as longevity rates increase. As Sarnowitz explains it, the real devil in this scenario is inflation.

For example, if someone starts retirement needing $3,000 a month at age 65, 3 percent inflation would mean they need $5,432 per month by the time they reach 85. Or, put another way, the loaf of bread that costs $3 today is going to cost $5.43 in 20 years.

“That short-sightedness could come at a cost,” Sarnowitz said. “Both longevity risk and inflation risk are real and without proper planning, many retirees are going to face a big shortfall between the amount they save and how much they actually need.”

What that means is retirees need to reconsider portfolios that shortchange stocks for the supposedly safer world of bonds in their retirement portfolios. Historically, stocks have been the only investment that have outpaced inflation. Sarnowitz urges investors to consider a diversified portfolio to offset the volatility that is inherent to stocks.

Retirement Risk Factor #2: Volatility

To minimize volatility, Sarnowitz recommends dusting off the notebook from that long-forgotten statistics course in college. By using the statistical measurement of standard deviation, an investor can determine whether or not their holdings are too volatile.

The higher the standard deviation of the portfolio from the average rate of return from year to year, the higher the volatility. And the higher the volatility, the higher the risk of portfolio failure in retirement.

Retirement Risk Factor #3: Sequence of Return

Simply put, the sequence of return risk means that if your portfolio loses money early in retirement, those losses are going to be amplified later on. Withdrawing $40,000 for your first year of retirement from a $1 million portfolio is much different than withdrawing $40,000 from a portfolio that has dipped to $900,000 because of a recession or poor stock performance.

Like volatility, investors can’t control sequence of return. But they can protect themselves from the risk by having a “safe bucket” of funds to withdraw from in the event of a dramatic downturn in the market.

That allows them to keep their principal stocks to wait out the market correction. Sarnowitz also pointed to research that shows such a safe bucket has a psychological benefit of making investors less likely to panic and sell stocks when the market dips, then have to rebuy them at highs.

“A proper buffer can consist of life insurance cash values, a reverse mortgage reserve account, cash or CDs, a guaranteed annuity, or any other account that will have a limited effect when there is a stock market downturn,” Sarnowitz said.

Retirement Risk Factor #4: Interest Rates

Bonds have an inverse relationship with interest rates: when interest rates are high, bond returns are low. And given that interest rates are at historic lows, bonds may be ready to fall from their highs.

“Investors expecting bond funds to perform as well in the next ten years as they have in the last ten will be disappointed,” Sarnowitz said, noting there may even be a risk for negative returns.

Bonds still have a place in a retirement portfolio, but probably not the half they occupied when the 4 percent rule was in fashion.

Sarnowitz urges his clients to find alternatives or ultimately rely on a portfolio invested more heavily in stocks which, in turn, increases volatility.

The New Safe Withdrawal Rule

A 2013 Morningstar report updated Bergen’s rule to say the safe withdrawal rate was 2.4 percent annually from a portfolio made up of 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds.

“We find a significant reduction in ‘safe’ initial withdrawal rates, with a 4 percent initial real withdrawal rate having approximately a 50 percent probability of success over a 30 year period,” according to the report’s executive summary.

The problem, of course, is that the landscape will eventually shift again and just like Bergen’s original 4 percent rule, the Morningstar recommendation will also be outdated.

A New Approach

For Sarnowitz, the answer has been advising clients to put a portion of their portfolio in fixed income annuities, which have been delivering steady returns since 1999. They also offer a hedge against volatility.

“Using FIAs, retirees have the potential to receive a percentage of the index return as interest credits with no risk of loss due to market declines,” he said. “It’s very important to understand that FIAs are a ‘safe money’ alternative to bonds offering absolute principle guarantees. This means that if the index loses value, the FIA will receive a zero percent interest credit in that year, but it will not suffer a loss to the original principle value.”

The Numbers Get Daunting

‘Rules of thumb’ can be helpful frameworks to help retirees think about spending and investing. They can also help those of us who haven’t yet retired by outlining how much we need to save before leaving the workforce. But keep this in mind – when it comes time to craft your actual budget for a year, you should calculate your actual costs. Markets fluctuate, costs sometime spike, and personal situations can change dramatically.

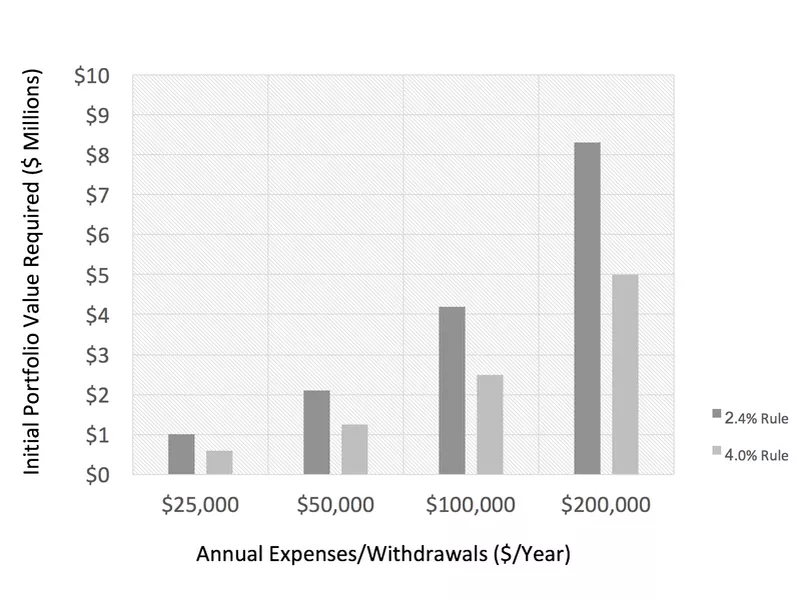

Here’s the thing… the numbers get daunting whether you’re following a 4 percent rule or Morningstar’s safer 2.4 percent rule. For example, following the traditional 4 percent rule, a retiree with a $1 million portfolio can spend a cost-of-living adjusted $40K per year, forever. But with only 2.4% in play, that annual budget shrinks to $24K.

Looking at it in reverse, if you think you’ll need $50K per year to cover adjusted expenses, the 4 percent rule suggests that you can retire once you’ve saved up $1.25 million while the 2.4 percent rule encourages you to keep punching that clock till you’ve saved $2.08 million.

Like we said… daunting.

Our best advice: start saving today.