Better Work-Life Balance? Try These Japanese Philosophies

If your work is creeping into dinner time or notifications buzzing through the weekend, Japan’s ancient wisdom might offer a few tools to help. While the country’s modern office culture is famously intense, its deeper traditions promote calm, clarity, and a healthy separation between duty and downtime. These 15 Japanese philosophies can reshape the way we approach work, rest, and everything in between.

Some Things Just Need to Be Accepted

Credit: Getty Images

Sometimes, what’s done is done. Uketamo, a word from Japan’s mountain monks, is about meeting reality head-on—even when it’s uncomfortable. Instead of stewing over what you can’t control, you let it land and move forward. That shift saves energy for what actually matters, both at work and outside of it.

Not Everything Has to Be Productive

Credit: iStockphoto

Work isn’t the only thing that deserves your time. The Japanese idea of asobi is about play for play’s sake. You’ll see it everywhere, from arcade games to comic books on the subway. Even a short daily break for something pointless can clear your head and bring back some spark.

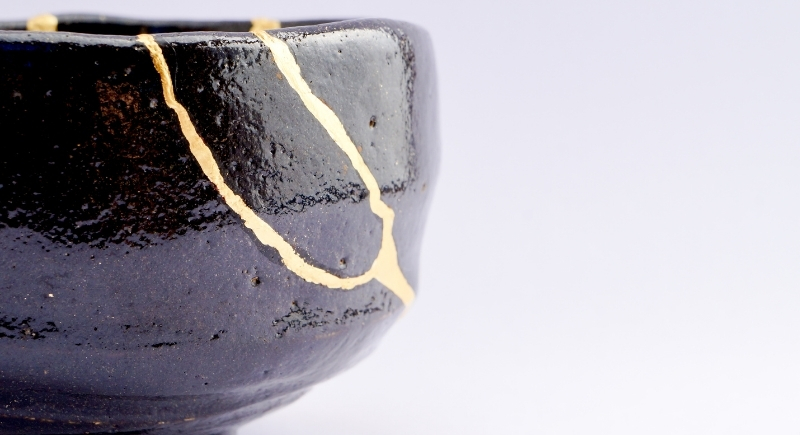

Cracks Aren’t Always Flaws

Credit: Getty Images

When pottery breaks in Japan, it’s often repaired with gold, not glue. This practice, known as Kintsugi, transforms damage into design. The same idea applies to mistakes at work or disappointments in life. Rather than hiding them, recognizing what you’ve learned from missteps can add value.

One Question Can Change the Evening

Credit: Canva

Before you close out your day, ask yourself: What did someone do for me today? That’s the core of Naikan, a Japanese practice that quietly shifts focus from complaints to gratitude. It’s used in therapy, even in prisons, and can help clear away the mental clutter work sometimes drags home. Over time, those little moments of reflection build stronger connections and make the tough days a bit easier to carry.

Play the Long Game When You’re Tired

Credit: iStockphoto

Staying calm through tough times has a name in Japan: Gaman. It refers to quiet perseverance during discomfort or adversity. Think of it as inner strength without the performance. Gaman doesn’t ask you to ignore problems, but it does help when challenges can’t be solved right away. It’s a mindset of riding things out with patience, dignity, and a focus on eventual stability.

You Don’t Have to Monetize What You Love

Credit: Getty Images

Ikigai refers to the joy or meaning behind why someone wakes up each day. For some, it’s work. For many others, it’s not. A 2010 survey in Japan showed that only 31% of respondents tied their ikigai to their job. The rest found it in things like family, hobbies, or community. The idea reminds us that purpose can be personal and doesn’t have to come with a paycheck.

Say Something Before It Becomes a Problem

Credit: iStockphoto

In Japanese work culture, Ho-Ren-So, short for report, inform, consult, is a communication model used to prevent issues from snowballing. The purpose is to keep information flowing before small problems grow. While designed for business, it translates easily to family life or friendships.

Look for What’s Already Enough

Credit: freepik

Mottainai is a Japanese way of seeing value in what’s already here—time, resources, even your own effort. It’s not just about wasting food or materials, but also wasting your attention and energy. Before chasing the next thing, take stock of what you have. Sometimes, “enough” is right in front of you, waiting to be noticed.

Not Every Space Needs to Be Filled

Credit: Getty Images

Between action and pause lies Ma, the value of space. In design, it’s the emptiness that shapes a room. In daily life, it’s the silence before speaking or the stillness between meetings. Western culture often sees pauses as wasted time, but Ma sees them as a necessary structure. Adding even a minute of intentional pause can help sharpen the next move.

When Cultures Collide, Harmony Is Possible

Credit: Getty Images

Take katsu curry: part French cutlet, part Indian spice, and fully Japanese. This kind of blend is called Nagomi, which is a harmonious fusion of differing elements. The same principle applies to work-life balance. Rather than forcing a hard divide, Nagomi allows different aspects of life to coexist smoothly.

It’s Okay to Feel a Little Bit Sad

Credit: iStockphoto

There’s a quiet sweetness to endings, and Mono no aware captures it. The term refers to an emotional awareness of life’s fleeting nature. That last cup of coffee before vacation, the sun setting on a busy day: those small transitions are often overlooked. But noticing them builds appreciation and presence. T

Waste Isn’t Just About Trash

Credit: Getty Images

Mottainai reflects a cultural regret over waste, not just food or materials, but time and effort too. Unused vacation days, abandoned hobbies, or half-eaten leftovers all fall under this umbrella. The idea promotes mindful use of resources and gratitude for what already exists. It’s been embraced by environmental movements worldwide, including the UN. Living with mottainai means taking nothing for granted and using what’s already enough.

Hospitality Isn’t Just for Guests

Credit: freepik

In Japan, everyday kindness goes beyond politeness. Omoiyari means thinking of others’ needs before they ask. It shows up in simple ways: refilling a water glass, sending a follow-up text, or helping without fanfare. At work, it builds smoother teams while at home, it deepens connections.

Small Changes Beat Sudden Overhauls

Credit: Getty Images

If a full lifestyle reset sounds exhausting, Kaizen offers another route. This method, used in Japanese businesses since the 1950s, promotes gradual, continuous improvement. It might be five extra minutes of stretching, slightly better lunch prep, or a tighter inbox system. Over time, the small wins add up.

You Don’t Have to Master Things All at Once

Credit: Canva

Shu-Ha-Ri breaks learning into three stages. First, follow the rules (shu). Then, start tweaking them (ha). Finally, evolve past them altogether (ri). Martial artists use this method, but so do designers and developers. It’s especially useful when adopting new routines. Structure helps early on, but too much rigidity can backfire. Shu-Ha-Ri leaves room for growth and creativity without rushing through the process.